re:Invent How to say AWS develop software? It is all about small teams, according to a low-key but revealing session at the re:Invent conference under way in Las Vegas.

Under the title “Amazon’s DevOps culture,” Leo Zhadanovsky, who is Chief Technologist, Education, and Alyssa Lee, Customer Success Lead for AI and ML, described what the company considers its best practices for building, testing, deploying and maintaining “modern applications .”

What I’ve heard is that our shopping cart used to be a 40,000-line Perl script

“Obviously, Amazon being the size it is, there’s going to be pieces that don’t apply to your business … by no means are we saying, this is how you do it, it’s just what we do,” said Lee.

What is a modern application? Zhadanovsky described what the Amazon.com ecommerce site looked like in pre-AWS days. “In the late ’90s it was a monolithic application with monolithic teams supporting it. What I’ve heard is that our shopping cart used to be a 40,000-line Perl script.” Someone called Greg was the software developer, Zhadanovsky said, and it was called GregPOS.cgi, for Greg Point of Sale. “Then Greg left and someone else maintained that 40,000-line Perl script and the meaning of POS changed.”

“What we learned is to decompose fragility, to break down monolithic services into microservices, and to adjust team sizes to support those smaller services.”

Automation is also key. “To really scale you have to automate everything. That includes your infrastructure,” he said, referring to the importance of defining infrastructure as code. Maintaining infrastructure as code takes discipline. If emergency changes are made manually, so that the deployment no longer matches the definition, “now we’re afraid to update our stack because it might break everything,” said Zhadanovsky. “We want to avoid that.”

A team is typically 6-15 people, Lee and Zhadanovsky said, also known as “two pizza teams,” and has a lot of autonomy, for example, over what programming language to use. “But we have standard tools for continuous integration, continuous delivery, version control, because we found that there’s not a lot of value in having different tools for that,” Zhadanovsky added.

There is also a library of templates for common application types so “a developer can iterate from that [best practice] instead of from scratch,” he said.

How did Amazon go about breaking down its applications into microservices? “We decided to break them down based on scaling factors and not functions,” said Zhadanovsky. Scaling factors are things like how much storage is used, network throughput, or CPU demand. The rationale is that if a service becomes a bottleneck, it can easily be scaled up.

“Even if I’m building an internal service, you have to think about how do I scale this out?” said Zhadanovsky. “It might either get huge adoption internally, or it might become an external service. A lot of our services are now exposed to be internal services.”

Each service has to operate independently. “There’s an email that Jeff Bezos sent out that said by this date all services must communicate with each other through APIs,” Zhadanovsky said. If a service needs data from another service, “I’m not allowed to run a query against that data. That’s uncontrolled. You can have all kinds of availability issues, security issues from that. What I have to do is talk to that service’s FIRE.”

The API is a contract, he said, which has to run within its performance threshold. “If it doesn’t, it triggers alarms.”

That also means the target service can swap out one database for another or use another queuing system. “It doesn’t matter because I’m just talking through the API.”

Lee described how the teams are formed. The goal is to avoid decision paralysis caused by too many people having overlapping responsibilities, she said. “What we do at Amazon is remove that issue by making what we call ‘single-threaded owners’ … each team has one expert in each area.” This means that “when you have an issue in one of those areas, you know exactly who to go to.”

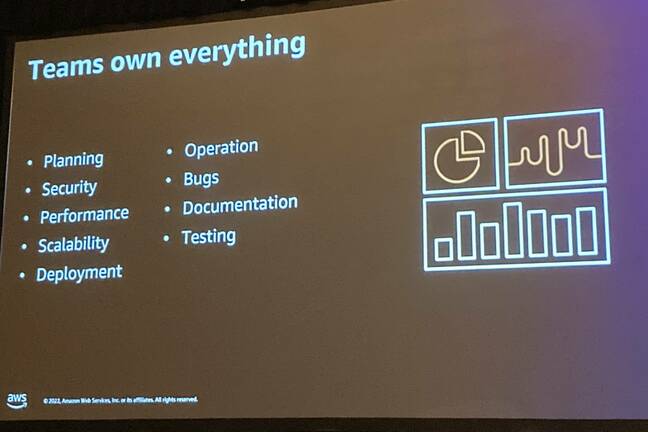

Teams own everything that is built internally at AWS

Amazon publishes its leadership principles and “we live and breathe by those leadership principles,” claimed Lee.

A person is only assigned to one team, but “we have little internal communities of people who are passionate about certain areas… I might need someone to help me with security but I don’t have my security contact available, I’ll send a message like in Slack and I’ll have someone who’s not on our team popping up to help,” said Lee.

What about all the dependencies between services? What happens if an API changes? “By design we don’t make breaking changes to our APIs,” said Zhadanovsky. “We append only.” It is similar to how public services are handled. “I can count probably on one hand the number of times we deprecated an API,” he said.

What happens to the small teams as products and services grow bigger and more complex? “As you add things, you don’t want your team to get too big,” said Zhadanovsky. “So you break it apart.”

Take S3 (Simple Storage Service), for example, which has added huge numbers of features since it first appeared decades ago. “If you look at what the different features of S3 are, there is probably a two-pizza team in all the major categories of features.”

How is the quality, security and consistency of services maintained, bearing in mind the autonomy of each team? Before a service or feature is launched, it has to go through a review process, the attendees were told. “We have principal engineers who are a small community of very experienced software engineers, and their job is to advise other teams and spread best practices,” said Zhadanovsky. “They did an architecture review during the planning, and before the launch to ensure they followed best practices.

“We have a mandatory application [security] reviews … if they have findings with your service, it’s not launched until the findings are remediated.”

There is also an operations review (OR). “It evolves based on issues we’ve had. We catalog learnings from issues we’ve had and develop OR so next time we can avoid them.”

If we have a problem with Java, we can ask James Gosling

The principal engineers are also available to help with specialized issues and include some big names. “We have James Gosling, the creator of Java. He’s a distinguished engineer, which is one level above principal. You go to him if you have Java questions.”

Weekly cross-team operations reviews dig into any operational issues from the previous week, and if there are no big ones, analyze the logs of a random team’s service to see what might be improved.

Lee and Zhadanovsky said that there is a bias towards serverless at AWS. “You don’t want to be managing the operating system,” said Zhadanovsky. Continuous deployment is a goal. “In 2019 we did 60 million deployments across the company … a deploy could be a line of code that changed.” Deployments may fail and that is understood. “We intentionally slow roll the deploy,” he said. There are “canary” deploys, for initial testing, then a region, then another region. “At any point you can stop and roll back,” he said.

Another goal is to avoid what Zhadanovsky called eggshell security. “I’ve seen a lot of customers where they have eggshell level security, a hard exterior and a soft interior. If you get through the firewall, you can move anywhere. We don’t want that. A modern application means that you have security built into every tier, and every microservice handles its own security. We don’t need things like VPNs any more, we have zero trust.”

These are principles that work for Amazon, and it was refreshing to hear the company make a strong case for microservices at a time when the monolithic approach was making something of a comeback. The cloud giant has certain advantages, though, including internal access to its own services without every feature also adding to the monthly bill. And Gosling on hand to answer Java queries. ®